If you’ve ever come across an old photograph like the one above, showing hospital patients resting in beds on a rooftop sun deck, you might wonder why such a setup existed. In the early to mid-20th century, many hospitals featured these sun decks, where patients were wheeled out to bask in natural sunlight and fresh air. This practice, now a curiosity in the age of modern medicine, was once considered a critical part of healing. Let’s explore why old hospitals prioritized sun exposure, how it was believed to benefit patients, and how our approach to healthcare has evolved since then.

The Era of Sunlight as Medicine

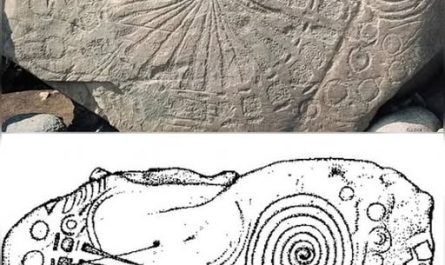

Before the widespread availability of antibiotics and advanced pharmaceuticals in the mid-20th century, medical treatments relied heavily on natural remedies. Sun decks in hospitals, often found on rooftops or open-air wards, were designed to harness the therapeutic power of sunlight and fresh air. This practice gained prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly during the fight against infectious diseases like tuberculosis (TB), which was a leading cause of death at the time.

The image above, showing rows of beds with patients exposed to the outdoors, reflects this philosophy. Hospitals, especially those treating respiratory illnesses, believed that sunlight and ventilation could boost the body’s natural defenses. TB sanatoriums, in particular, popularized this approach, with patients spending hours outdoors regardless of the weather, often wrapped in blankets to stay warm. The idea was simple: sunlight provided a natural disinfectant, while fresh air helped clear the lungs of harmful pathogens.

The Science Behind the Sun Deck

At the time, medical professionals had observed that patients exposed to sunlight often showed improved recovery rates. This wasn’t just folklore—there was some scientific basis to support it. Sunlight is a rich source of ultraviolet (UV) rays, which can kill or inhibit the growth of bacteria and other microbes. In the pre-antibiotic era, this natural sterilization was a valuable tool against infections. Additionally, sunlight triggers the body to produce vitamin D, which supports bone health and boosts the immune system—crucial for patients weakened by illness.

Fresh air was equally important. Crowded, poorly ventilated indoor spaces were breeding grounds for disease, especially in the days before modern HVAC systems. By moving patients outside, hospitals aimed to reduce the spread of infections and improve overall well-being. The open-air treatment was so widely accepted that it influenced hospital architecture, with designs incorporating large windows, verandas, and rooftop decks to maximize exposure to the elements.

A Holistic Approach to Healing

The use of sun decks also reflected a broader, more holistic approach to medicine. Doctors of the era emphasized the importance of rest, nutrition, and environmental factors alongside medical care. Patients on sun decks were often encouraged to rest for long periods, allowing their bodies to recover naturally. This was particularly true for TB patients, whose treatment regimens included months or even years of outdoor exposure, combined with a nutritious diet to rebuild strength.

The image captures this serene, almost meditative atmosphere, with patients lying in orderly rows, surrounded by the open sky. The architecture—featuring sturdy railings and shaded areas—suggests a deliberate effort to create a safe, controlled outdoor environment. For many, the psychological benefits of being outside, away from the sterile confines of indoor wards, were as valuable as the physical effects.

The Shift Away from Sun Decks

Today, the sight of patients on a sun deck might seem unusual, even impractical. The decline of this practice began with the advent of penicillin in the 1940s, which revolutionized treatment for bacterial infections like TB. Antibiotics and other pharmaceuticals offered faster, more targeted solutions, reducing the reliance on natural remedies. As medical technology advanced, hospitals shifted focus to indoor care, equipped with climate control, sterile environments, and sophisticated equipment.

Modern healthcare also prioritizes protection from UV radiation, which can cause skin damage and increase the risk of skin cancer with prolonged exposure. The emphasis has moved toward controlled indoor settings, where patients are shielded from environmental variables. While fresh air and sunlight remain beneficial, they are no longer seen as primary treatments, overshadowed by the precision of modern medicine.

A Lost Tradition?

The shift away from sun decks raises an interesting question: have we lost something valuable? The image and the accompanying text suggest a nostalgia for a time when hospitals embraced nature’s healing power. Today, we often avoid sunlight, slathering on sunscreen and staying indoors, yet studies continue to highlight the benefits of moderate sun exposure for vitamin D production and mental health. The contrast between past and present prompts reflection—could there be a middle ground where we integrate natural elements into modern healthcare?

Some hospitals and wellness centers have begun reintroducing outdoor spaces, like gardens or solariums, recognizing their role in patient recovery. However, the grand sun decks of old are unlikely to return, replaced by a more cautious, technology-driven approach to healing.

Conclusion

The sun decks of old hospitals, as seen in the photograph, were a product of their time—a time when sunlight and fresh air were considered essential medicine. Before pharmaceuticals took center stage, these outdoor spaces offered a natural, holistic way to combat disease and promote recovery, particularly for conditions like tuberculosis. The image of patients resting under the open sky reminds us of a simpler era in healthcare, one that valued nature’s role in healing. While modern medicine has moved away from this practice, the legacy of sun decks invites us to reconsider the balance between technology and the natural world in our pursuit of health.