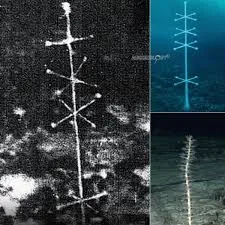

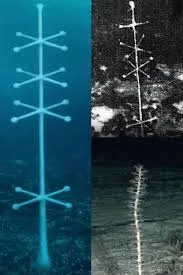

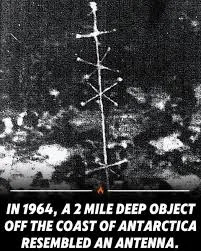

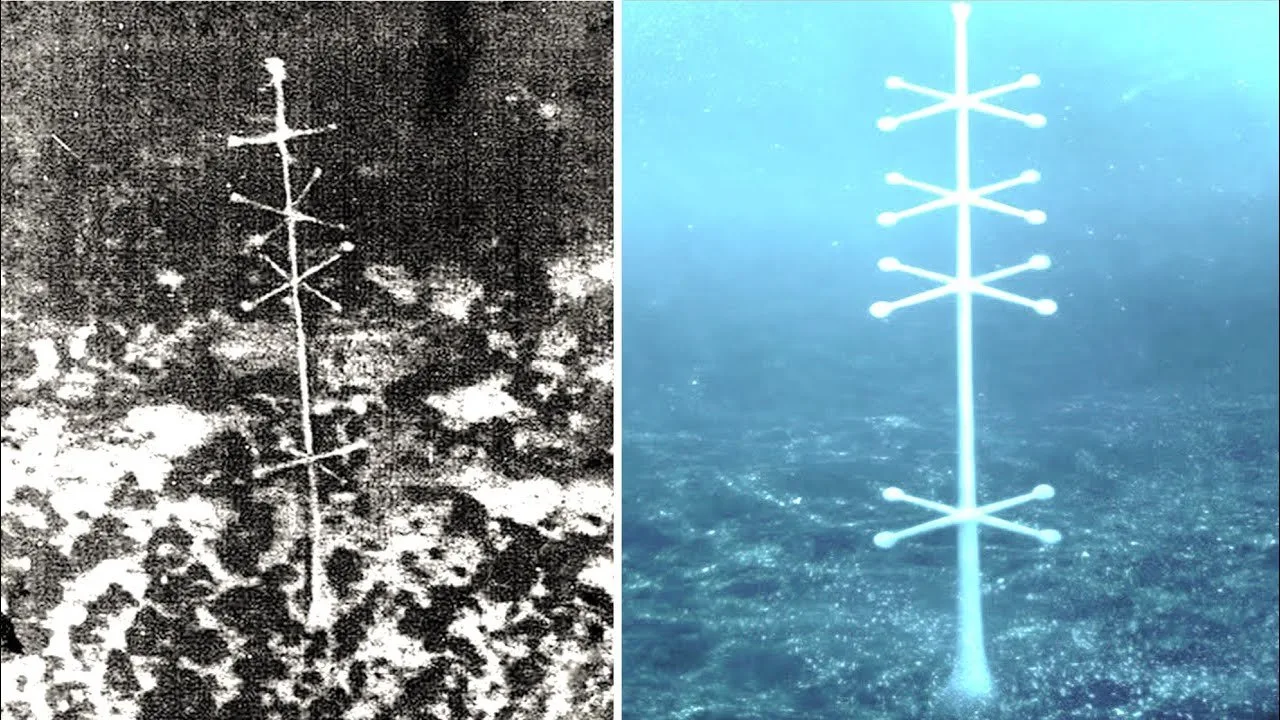

On August 29, 1964, the USNS Eltanin, an Antarctic oceanographic research vessel, captured a single, haunting photograph of a peculiar antenna-like object standing upright on the seafloor, 3,904 meters (12,808 feet) deep, west of Cape Horn at coordinates 59°07’S, 105°03’W. Its mechanical appearance sparked wild speculation about alien technology or ancient civilizations, captivating UFO enthusiasts and fringe theorists. Identified in 1971 by oceanographers Bruce C. Heezen and Charles D. Hollister as a carnivorous deep-sea sponge, Chondrocladia concrescens (formerly Cladorhiza concrescens), the so-called Eltanin Antenna remains shrouded in mystery due to the lack of follow-up missions and the solitary nature of the image. This enigmatic relic, like other out-of-place artifacts, continues to fuel debate about the ocean’s unexplored depths.

The Discovery and Initial Frenzy

The USNS Eltanin, a 1,850-ton icebreaking research ship launched in 1957, was photographing the seabed as part of its Antarctic surveys when it captured the image. The object, roughly 2 feet tall, resembled a telemetry antenna with a central stalk and radiating spokes, standing eerily upright in the sediment. First publicized in the New Zealand Herald on December 5, 1964, under the headline “Puzzle Picture From Sea Bed,” the photograph ignited public imagination. By 1968, author Brad Steiger, in Saga Magazine, described it as “an astonishing piece of machinery,” fueling theories of extraterrestrial artifacts or lost technologies, with proponents like Bruce Cathie suggesting it was evidence of an ancient grid system.

The solitary nature of the photograph—no additional images or samples were taken—amplified speculation. The Eltanin’s crew, including senior marine biologist Thomas Hopkins, initially doubted it was a biological organism due to its depth and symmetry, with Hopkins questioning how a man-made object could end up 4 km underwater. The lack of return missions, due to the site’s remoteness and the era’s limited deep-sea technology, left the object unstudied, cementing its status as a mystery.

Scientific Identification: A Sponge in Disguise

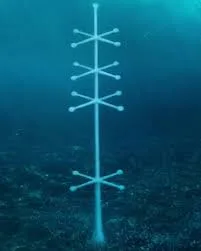

In 1971, Heezen and Hollister’s book The Face of the Deep identified the object as Chondrocladia concrescens, a carnivorous sponge first described by Alexander Agassiz in 1888. This deep-sea species, part of the Cladorhizidae family, has a tree-like structure with a long stem anchored by root-like rhizoids and club-like appendages radiating from nodes, resembling a microwave antenna. Its filaments, tipped with sticky hooks, capture tiny crustaceans in nutrient-scarce depths, with symbiotic microbes aiding digestion. The sponge’s upright, symmetrical form, up to 2 feet tall, explains its mechanical appearance, especially in a single, low-resolution image.

Further confirmation came in 2003 when marine biologist Tom DeMary, investigating UFO claims, contacted A.F. Amos, an Eltanin oceanographer, who reaffirmed the sponge identification, citing Heezen and Hollister’s work. Modern studies, including high-resolution imaging and genetic sequencing, have solidified Chondrocladia’s classification, with its adaptations optimized for deep-sea survival. The solitary appearance in the photograph, unlike the “bushes” of sponges described by Agassiz, likely contributed to early confusion, as did the era’s limited knowledge of deep-sea ecosystems.

Lingering Questions and Alternative Theories

Despite the scientific consensus, the Eltanin Antenna’s mystery persists. The single photograph, taken with a towed camera sled, lacks context—no other images or physical samples exist to confirm the sponge’s presence at the site. The extreme depth, 3,904 meters, where pressures exceed 5,600 psi, makes human-made artifacts unlikely but not impossible, as shipwrecks and debris have been found at similar depths. Fringe theorists argue the object’s symmetry and isolation suggest advanced technology, drawing parallels to the Coso Artifact’s misidentification or speculative claims about Baalbek’s stones. The absence of follow-up missions, due to logistical challenges and shifting research priorities, fuels skepticism, with some questioning whether the sponge identification was a convenient dismissal.

Recent deep-sea exploration, like the 2025 black seadevil sighting off Tenerife, underscores how little we know about the ocean, which covers 71% of Earth’s surface yet remains 80% unmapped. The Eltanin Antenna, like the black seadevil, highlights the ocean’s capacity to surprise, with creatures like Chondrocladia mimicking artificial structures in ways that challenge perception.

Lessons for Today

The Eltanin Antenna, like the Dahomey Amazons’ cornrow maps or the Jadeite Cabbage’s artistry, reflects humanity’s drive to interpret the unknown. Its lessons include:

Critical Inquiry: The sponge identification teaches us to balance wonder with evidence, urging rigorous scrutiny of extraordinary claims, akin to debunking the Coso Artifact.

Ocean Exploration: The mystery underscores the need for deep-sea research, inspiring missions like those to HIMI or the Mariana Trench to uncover hidden ecosystems.

Cultural Imagination: Like Samir and Muhammad’s story, the antenna’s allure shows how narratives shape perception, encouraging us to question assumptions while embracing curiosity.

A Persistent Enigma

The Eltanin Antenna, captured in a single 1964 photograph, remains a deep-sea riddle, its antenna-like form blurring the line between nature and mystery. Identified as a Chondrocladia sponge, it nonetheless sparks debate, its solitary image echoing the haunting gaze of the Medusa head or the spearhead in bone’s brutal truth. As the ocean continues to guard its secrets, this relic reminds us that even in our age of exploration, the abyss holds stories yet to be told, daring us to dive deeper.