Mummified Moa Claw Unearthed in New Zealand Cave Rewrites Extinction Timeline

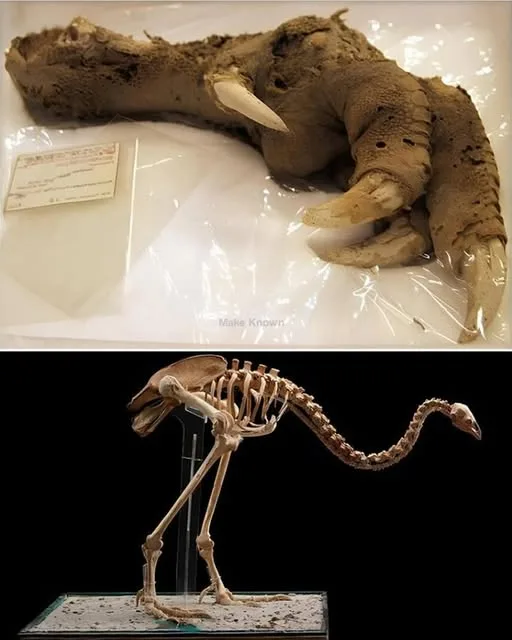

In 1987, a group of explorers delving into the depths of a cave system in New Zealand’s Mount Owen, within Kahurangi National Park, stumbled upon an extraordinary find: a mummified claw of an upland moa, complete with preserved muscle, skin, and sinew. This remarkable artifact, belonging to a species believed to have vanished around 600 years ago due to human settlement and overhunting, has challenged long-held assumptions about the extinction of these giant flightless birds. The claw’s exceptional preservation, likely due to the cave’s cold, dry conditions, has sparked speculation that moa may have survived in remote regions longer than previously thought, offering a tantalizing glimpse into New Zealand’s prehistoric past.

A Window into a Lost World

The upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus), one of nine moa species that once roamed New Zealand’s forests and mountains, was a smaller member of this extinct family, standing about 1.3 meters (4.3 feet) tall. These flightless birds, unique to New Zealand, ranged from turkey-sized to the towering Dinornis, which reached 3.6 meters (12 feet). By the time Polynesian settlers arrived around 1280 AD, followed by Europeans in the 19th century, moa populations plummeted due to hunting, habitat destruction, and predation by introduced species. Most researchers pegged their extinction to around 1400–1500 AD, with no confirmed sightings thereafter.

The 1987 discovery in Honeycomb Hill Cave, a vast limestone network, upended this timeline. The claw, found by a team from the Canterbury Museum, was in near-perfect condition, with desiccated flesh, sinew, and scaly skin still intact, resembling a freshly preserved specimen rather than a relic centuries old. Radiocarbon dating placed the claw at approximately 600–800 years old, aligning with the presumed extinction period, but its pristine state suggested it could have been younger, raising questions about whether small moa populations lingered in isolated areas.

Preservation by Nature’s Freezer

The claw’s remarkable preservation is attributed to the unique conditions of Honeycomb Hill Cave. The cave’s cold, dry environment, with stable temperatures and low humidity, acted as a natural mummification chamber, preventing bacterial decay and preserving organic material. Similar finds, like moa feathers, skin, and even mummified remains, have been uncovered in other New Zealand caves, but the Mount Owen claw stands out for its completeness. The presence of muscle and sinew suggests the bird died in or near the cave, possibly trapped or seeking shelter, and was quickly sealed from external elements.

This find echoes other discoveries in New Zealand’s caves and bogs, where moa bones, eggshells, and soft tissues have been preserved. The claw, now housed at the Canterbury Museum, offers a rare opportunity to study the upland moa’s anatomy, diet, and environment, providing clues about its adaptations to the rugged South Island terrain.

Did Moa Survive Longer Than Thought?

The claw’s condition has fueled speculation that upland moa, adapted to remote, mountainous regions, may have evaded extinction longer than their lowland cousins. Historical accounts, such as Māori oral traditions and unconfirmed European sightings in the 19th century, hint at moa persisting in isolated pockets. For instance, a 1993 report of large bird tracks in the Craigieburn Range and alleged sightings in Fiordland have kept the idea of “crypto-moa” alive, though no definitive evidence supports post-1500 survival.

Genetic studies and pollen analysis suggest moa habitats shrank as forests were cleared by early Māori settlers, but the rugged northwest Nelson region, where Mount Owen lies, remained sparsely populated. The claw’s preservation suggests it could have belonged to a bird that died relatively recently in geological terms, prompting researchers to reconsider whether small, elusive populations survived into the 16th or even 17th century in such remote areas.

A Scientific and Cultural Treasure

The mummified claw is more than a scientific curiosity; it holds cultural significance for New Zealand’s Māori, who view moa as part of their ancestral heritage. Moa were a vital food source and cultural symbol, with their bones used for tools and ornaments. The discovery underscores the importance of protecting New Zealand’s archaeological sites, as caves like Honeycomb Hill continue to yield clues about the country’s prehuman ecosystems.

Ongoing research, including DNA analysis of the claw’s tissues, could reveal more about the upland moa’s genetic diversity and extinction timeline. Scientists are also exploring whether environmental DNA (eDNA) in cave sediments could indicate how long moa persisted. Such studies may clarify whether these birds were truly gone by 1500 or if they clung to survival in New Zealand’s wild interior.

A Legacy of the Lost

The Mount Owen moa claw, with its hauntingly preserved flesh, is a poignant reminder of a world lost to human impact. It challenges us to rethink the extinction of New Zealand’s iconic megafauna and highlights the power of natural preservation to bridge millennia. As researchers probe the secrets of this relic, the claw stands as a testament to the upland moa’s resilience and the enduring mysteries of New Zealand’s ancient landscapes, inviting us to imagine a time when giant birds roamed the earth.