In May 2007, an indigenous Nenets hunter and reindeer herder, Yuri Khudi, and his three sons made an extraordinary discovery on the banks of the frozen Yuribey River in Siberia’s Yamal Peninsula: the remarkably preserved remains of Lyuba, a female woolly mammoth calf who lived for just 30–35 days around 41,800 years ago. This 1-month-old mammoth, the best-preserved specimen of her kind ever found, offers an unparalleled glimpse into the life and death of these Ice Age giants, revealing intimate details about her biology, diet, and demise.

A Miraculous Preservation

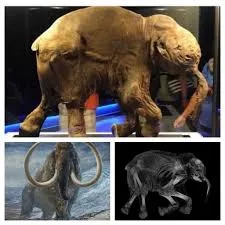

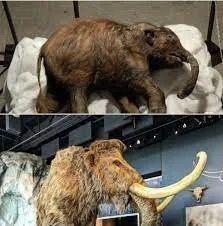

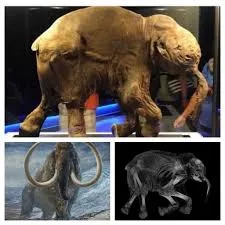

Lyuba’s pristine condition is a marvel of natural preservation. Standing 33.5 inches (85 cm) tall and measuring 51 inches (130 cm) from trunk to tail, she weighed about 110 pounds (50 kg)—roughly the size of a large dog. Her body was preserved by a unique combination of environmental factors and biochemistry. Scientists determined that lactic acid, produced by bacteria that entered her body shortly after death, acted as a natural preservative, protecting her soft tissues, fur, and organs from decay in the permafrost. This rare process kept Lyuba’s remains nearly intact, with her reddish-brown wool, tiny trunk, and even eyelashes still visible.

A CT scan conducted by researchers, including teams from the University of Michigan and Russia’s Zoological Institute, revealed astonishing details. Lyuba’s organs, including her heart, liver, and intestines, were preserved, and her digestive tract contained traces of adult mammoth feces. This finding confirmed that baby mammoths, like modern elephants, consumed their mother’s feces to acquire essential gut microbes for digesting tough grasses—a critical adaptation for their herbivorous diet.

A Tragic End

The scan also pinpointed Lyuba’s cause of death: drowning in muddy water. Fine sediment found in her trunk, throat, and lungs suggests she became trapped in a riverbed’s thick mud, suffocating as she inhaled the slurry. This tragic accident, likely during a spring thaw when rivers swelled, preserved her body in the cold, oxygen-poor mud, which later froze in Siberia’s permafrost, locking her in time for over 40,000 years.

A Window into the Ice Age

Lyuba’s discovery, dated to approximately 41,800 years ago via radiocarbon analysis, places her in the Late Pleistocene, when woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) roamed the grassy steppes alongside other megafauna like bison and reindeer. Her small size and short life indicate she was born in a harsh, cold environment, reliant on her mother’s milk and warmth. The presence of adult feces in her stomach suggests she was just beginning the transition to solid food, a vulnerable stage for mammoth calves.

Found in the Yamal Peninsula, a region rich in mammoth fossils, Lyuba’s preservation stands out. Unlike fragmented bones or tusks, her near-complete body offers a rare opportunity to study mammoth anatomy and behavior. Her discovery challenges earlier assumptions about mammoth calf mortality, showing that environmental hazards like rivers posed significant risks, even to well-protected herd members.

A Global Treasure

Named “Lyuba” (meaning “love” in Russian) after Yuri Khudi’s wife, the calf has become a scientific and cultural icon. After her discovery, she was studied in Russia and Japan, with exhibitions drawing crowds at museums like the Field Museum in Chicago. Now housed at the Shemanovsky Museum in Salekhard, Russia, Lyuba continues to captivate researchers and visitors, her tiny form a poignant reminder of a lost world.

Lyuba’s story is more than a fossil find—it’s a bridge to the Ice Age, revealing the fragility and resilience of life in a frozen wilderness. Her perfectly preserved body, down to the traces of her last meal, speaks to the power of nature’s deep freeze and the enduring curiosity of those who uncover its secrets.