Nestled in the West Bank near the Jordan River, Jericho holds the distinction of being one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited settlements, with roots stretching back to around 10,000 BCE. Archaeological excavations have illuminated its profound historical significance, revealing Jericho’s role as a pioneer in permanent human settlements and the dawn of civilization. From its Neolithic origins to its prominence under Herod the Great and its evolution through the Crusader era, Jericho’s layered history reflects the resilience and adaptability of human society.

A Neolithic Milestone

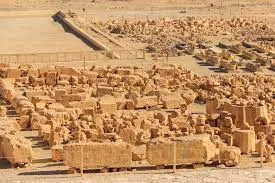

Jericho’s story begins in the Natufian period (c. 10,000 BCE), when hunter-gatherers transitioned to sedentary life. Excavations, notably by Kathleen Kenyon in the 1950s, uncovered the iconic Round Tower and defensive walls at Tell es-Sultan, dating to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA, 8500–7300 BCE). These structures, among the earliest known, suggest a sophisticated community of up to 2,000 people who practiced early agriculture, cultivating wheat and barley, and built communal defenses—possibly against floods or rival groups. The plastered skulls found in caches, adorned with shells for eyes, hint at complex spiritual practices, perhaps ancestor veneration, marking Jericho as a cradle of cultural innovation.

By the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (7300–6000 BCE), Jericho’s inhabitants constructed rectangular homes and expanded irrigation, supporting a thriving settlement. Its location, fed by the fertile oasis of Ain es-Sultan (Elisha’s Spring), made it an ideal hub in the arid Jordan Valley, fostering trade and stability.

Herodian Jericho: A Roman-Inspired Retreat

In 4 BCE, Herod the Great, the Roman client king of Judea, transformed Jericho into his winter residence, capitalizing on its mild climate and lush surroundings. Located about a mile south of the ancient tell, Herodian Jericho, explored through 1950–1951 excavations by John Pritchard and Ehud Netzer, showcased Roman architectural grandeur. A monumental façade along Wadi Al-Qilṭ, likely part of Herod’s opulent palace, featured opus reticulatum (diamond-patterned brickwork) and frescoes, blending Roman engineering with local stone. The palace complex included sunken gardens, bathhouses, and aqueducts, fed by the wadi’s springs, reflecting Herod’s penchant for luxury and his alignment with Roman aesthetics.

This site, distinct from Old Testament Jericho, became a key setting in Roman and New Testament narratives. Herod’s winter court hosted political intrigues, and the nearby Hasmonean palaces, expanded by Herod, linked Jericho to events like the baptism of Jesus in the nearby Jordan River (John 1:28). Tragically, Herod died in Jericho in 4 BCE, cementing its historical weight.

Crusader Shift and Modern Jericho

By the Crusader period (11th–13th centuries CE), Jericho had shifted approximately a mile east of Tell es-Sultan, laying the foundation for the modern town. This relocation, near the Byzantine-era synagogue and Islamic-era structures like the 8th-century Umayyad palace at Khirbet al-Mafjar, reflected changing political and economic realities. The Crusaders built mills and fortifications, capitalizing on Jericho’s fertility, known for date palms and sugar cane. The modern town, now home to about 20,000 residents, grew around this medieval nucleus, with Ain es-Sultan still providing water.

A Legacy Etched in Time

Jericho’s enduring inhabitation, from its Neolithic walls to Herod’s palatial retreat and its Crusader rebirth, underscores its unique place in human history. Archaeological finds—stone towers, Roman façades, and medieval mills—reveal a city that adapted to environmental and political shifts while remaining a vital oasis. As a UNESCO World Heritage nominee and a site of biblical and cultural resonance, Jericho continues to captivate, offering a 12,000-year testament to humanity’s ability to build, endure, and reimagine life in one of Earth’s oldest cities.