Beneath the bustling streets of San Francisco’s Financial District and Embarcadero, a hidden fleet of 19th-century ships lies entombed, silent relics of the California Gold Rush (1848–1855). These vessels, once brimming with gold-crazed prospectors, now rest under skyscrapers, sidewalks, and subway lines, their wooden hulls preserved in the mud of what was once Yerba Buena Cove. Daily, thousands of commuters ride Muni Metro streetcars or walk the pavements, unaware they’re crossing the skeletal remains of ships that carried dreams of fortune. In recent years, the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park has unveiled a new cartographic depiction, updating the original 1963 map with modern archaeological discoveries, bringing this lost maritime history back into focus. This is the story of San Francisco’s “Gold Rush Pompeii,” a buried testament to a city built on ambition and adventure.

The Gold Rush and a Forest of Masts

When gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848, word spread like wildfire, sparking one of the greatest migrations in history. By 1849, nearly 1,000 ships sailed into San Francisco (then called Yerba Buena), carrying tens of thousands of prospectors—known as “Forty-Niners”—from the U.S., Australia, China, Chile, and beyond. The Canopic Mouth of the San Francisco Bay, once a shallow cove lapping at what is now Montgomery Street, became a “forest of masts,” with hundreds of vessels crammed together. Crews and passengers often abandoned their ships, lured by the promise of gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills, leaving the harbor glutted with idle hulks.

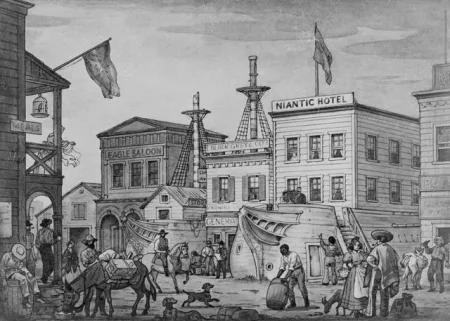

Yerba Buena Cove, described by chroniclers as a chaotic tangle of ships, was transformed as San Francisco grew. Entrepreneurs saw opportunity in the abandoned vessels, converting them into storeships, warehouses, hotels, saloons, and even jails. Others were deliberately scuttled to claim land under lax 19th-century laws, which allowed owners to secure valuable waterfront plots by sinking ships and filling the cove with debris and sand. By the 1850s, the cove was filled in, extending the city’s shoreline to the modern Embarcadero, and the ships were buried beneath new streets and buildings.

A Hidden Fleet Rediscovered

Estimates suggest 40 to 70 ships remain entombed beneath San Francisco, with over 200 likely buried during the Gold Rush era. Modern construction projects have unearthed many, revealing a subterranean archive of maritime history:

-

Niantic (1849): A whaling ship turned storeship, saloon, and hotel, run aground at Clay and Sansome Streets. Burned in the 1851 fire, its hull was rediscovered in 1978 under the Transamerica Pyramid, yielding artifacts like 1844 champagne bottles (sadly undrinkable). A plaque marks the site today.

-

Rome (1990s): A massive ship found during Muni Metro tunnel construction south of Market Street, now passed daily by N-Judah, T, and K streetcar lines through its forward hull. It was intentionally scuttled for land rights near Justin Herman Plaza.

-

General Harrison (2001): Unearthed at Battery and Clay Streets under the Club Quarters Hotel, this storeship’s remains included ash and melted glass from the 1851 fire, now commemorated with sidewalk nails and a hull sculpture.

-

Apollo (1920s): Discovered with coins and a gold nugget at Sacramento Street, its stem timber is displayed at the Maritime Visitors Center.

-

Charles Hare’s Ship-Breaking Yard: Located at Rincon Point near the Bay Bridge, this salvage operation, employing over 100 Chinese workers, dismantled ships like the Candace at Spear and Folsom Streets, leaving remnants uncovered in modern excavations.

These discoveries, often triggered by construction for high-rises or transit lines, reveal ships preserved in the seawater-saturated mud of the original bay floor, where tides still rise and fall beneath the city.

The New Cartographic Depiction

In 2024, the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park released an updated map of these buried ships, building on the original 1963 map that identified 42 storeships. Crafted with input from archaeologists like James Allan, James Delgado, and Allen Pastron, the new map incorporates recent finds and marks confirmed sites with red circles. Notable additions include:

-

Rincon Point Ship-Breaking Yard: Highlighted at the southern end of Yerba Buena Cove, where Charles Hare ran a profitable salvage operation.

-

Galapagos Tortoise Bones (2006): Found at Broadway and Front Streets, marked with an asterisk, these bones from an 1820s ship suggest crews stopped at the Galapagos Islands for food, with surplus tortoise meat served as turtle soup in local eateries.

-

Sydney Town and Little Chile: The map details cultural enclaves like Sydney Town (where 7,500 Australians settled) and Little Chile, reflecting the diverse Gold Rush population of 20,000 Chinese, Chileans, and others by 1852.

Displayed at the Maritime Visitors Center at Hyde Street Pier, this map traces San Francisco’s shifting shoreline from 1849 to 1857, showing how the filled-in cove buried these maritime relics. It draws on research from Ron S. Filion’s 2023 book, Buried Ships of San Francisco, which catalogs over 70 ships using archives, newspapers, and archaeological data.

Why Were the Ships Buried?

The entombment of these ships was no accident but a product of necessity and opportunism. San Francisco’s real estate boom during the Gold Rush made waterfront land as valuable as gold. By sinking ships or building piers over them, speculators created new plots as the cove was filled with sand, debris, and even burned ship remains after the 1851 fire that razed much of the city. This land-grab strategy, while ingenious, led to occasional skirmishes and gunfights over disputed claims. The Niantic, for example, became a hotel at Clay and Sansome, now six blocks from the current shoreline, while the Arkansas was repurposed as the Old Ship Saloon at 298 Pacific Avenue.

Geologically, the filled cove remains unstable, prone to liquefaction during earthquakes, as seen with the Millennium Tower’s tilting issues near the former cove’s edge. The buried ships, preserved in mud, are a reminder of this precarious foundation, with seawater tides still affecting the subterranean landscape.

A Subterranean Legacy

The buried ships of San Francisco are more than relics; they’re a “Gold Rush Pompeii,” as archaeologist James Delgado calls them, preserving the chaotic ambition of the 1840s and 1850s. The San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park’s updated map, enriched by modern archaeology, invites us to look beneath the city’s surface, where the Niantic, Rome, General Harrison, and dozens more lie entombed. These ships, once vessels of hope, now anchor San Francisco’s history, reminding us of the dreams that built a city—and the fragile ground on which it stands.

As you ride the Muni Metro or stroll past the Transamerica Pyramid, pause to imagine the creaking hulls below, still touched by the tides of a vanished cove. San Francisco’s streets are not just pavement but a palimpsest of the past, where the ghosts of the Gold Rush still sail in silence.