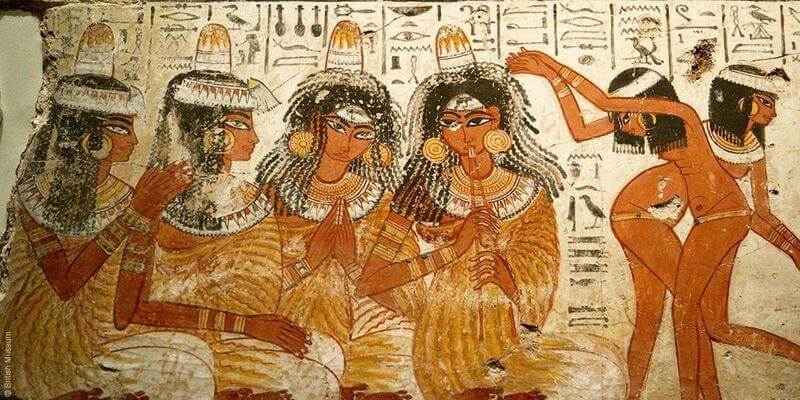

Pregnancy tests have never been something people look forward to, and even today, they’re usually taken in moments of anxiety or uncertainty. But this experience is far from modern—pregnancy tests have been around since Ancient Egypt, and astonishingly, they were more advanced than many would expect.

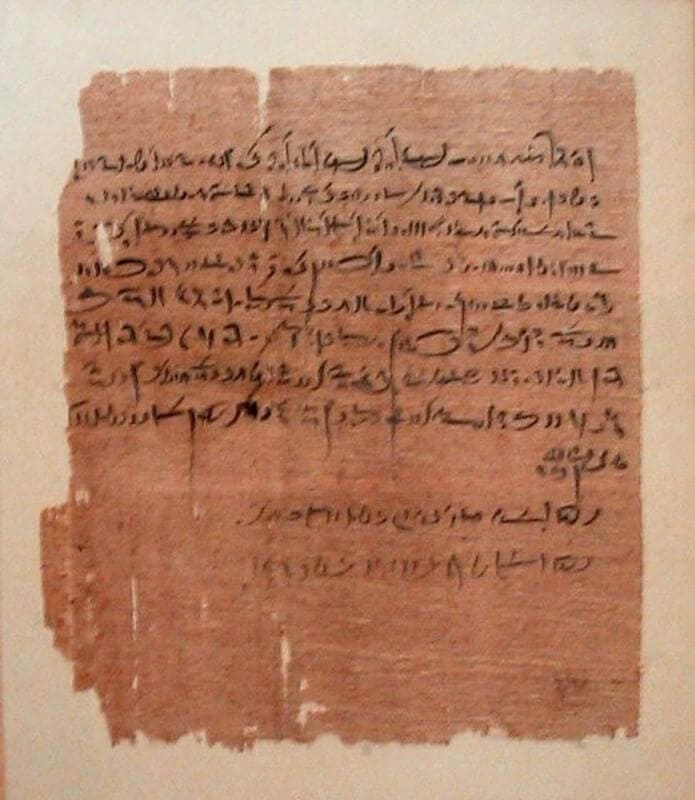

Over 3,500 years ago, Ancient Egyptian women were already using urine-based pregnancy tests. Their method didn’t involve plastic sticks or hormone strips but relied instead on sprouting grains. Women would urinate on bags of barley and emmer wheat, and if either bag began to sprout, it was a strong sign of pregnancy. Even more impressively, the Egyptians believed the first grain to sprout would reveal the baby’s gender: barley for a boy, and emmer wheat for a girl.

This method was surprisingly accurate for its time—studies estimate it was around 70% effective, which is remarkable considering the limited scientific tools available. While modern scientists view this method with some skepticism, especially concerning gender prediction, the technique shows how closely ancient civilizations observed nature and human biology.

Urine has long been linked to fertility in various cultures. In medieval Europe, “piss prophets” (yes, that was the real term) used urine mixed with wine to diagnose pregnancy. They even burned urine-soaked cloth to see if a woman would gag from the smell—a sign she might be pregnant. These bizarre methods all point to a centuries-old belief in the diagnostic power of urine, a belief rooted in the practices of Ancient Egypt.

Ancient Egyptian women may have had higher estrogen levels than modern women, which could explain why their grain-based tests seemed more effective. Although the barley vs. wheat method isn’t reliable by today’s scientific standards, it demonstrates a profound curiosity and empirical approach to medicine. It’s fascinating to imagine what more they might have achieved had their scientific exploration continued uninterrupted.

Beyond pregnancy, ancient Egyptian medicine left a significant mark on future civilizations. According to scholar Sofie Schidt, Ph.D., many Egyptian medical practices found their way into Greek, Roman, and even medieval texts—some ideas tracing all the way to pre-modern medicine.

Ancient Egyptian health practices also reflected their harsh realities. Infant mortality rates were high, and children faced life-threatening challenges before the age of five. Once they survived early childhood, life expectancy averaged around 29 years for women and 33 for men. Despite the tough conditions, Egyptians breastfed their children for long periods to boost immunity, and even in unsanitary conditions, they made efforts to protect young lives.

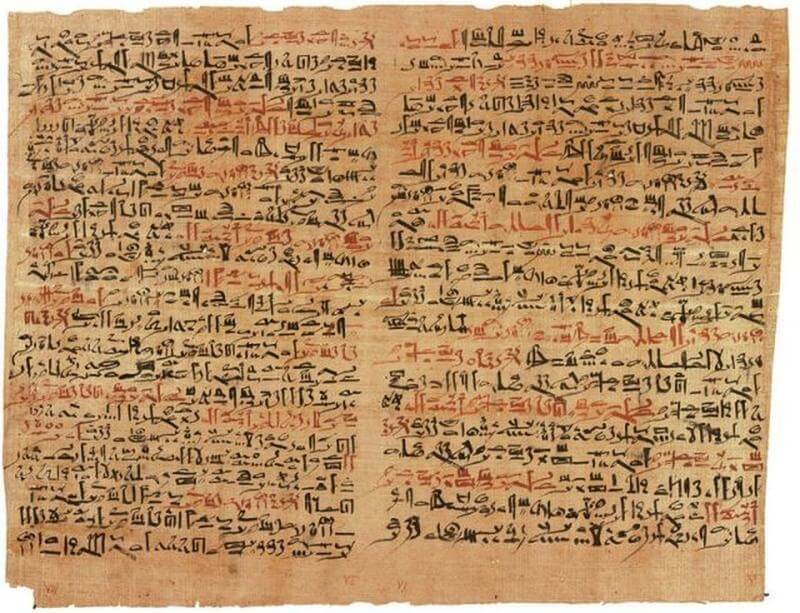

Few ancient texts survive today, but what remains reveals a surprisingly advanced understanding of the human body and its processes. The pregnancy test described in ancient papyri is just one example of how ahead of their time the Egyptians truly were.

Interestingly, many of the gender myths we still hear today—like sweet cravings meaning a girl or glowing skin indicating a boy—aren’t so different from the barley vs. wheat test. Our fascination with predicting the unknown hasn’t changed, even if our methods have.