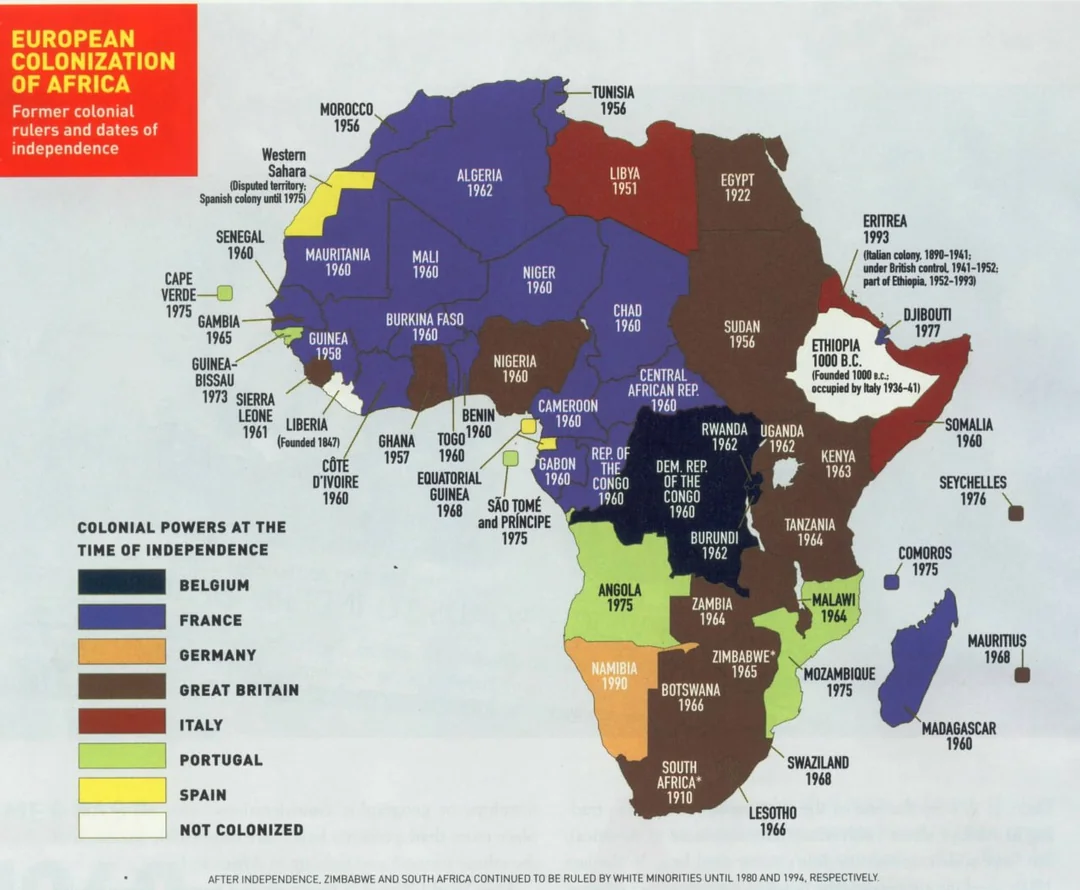

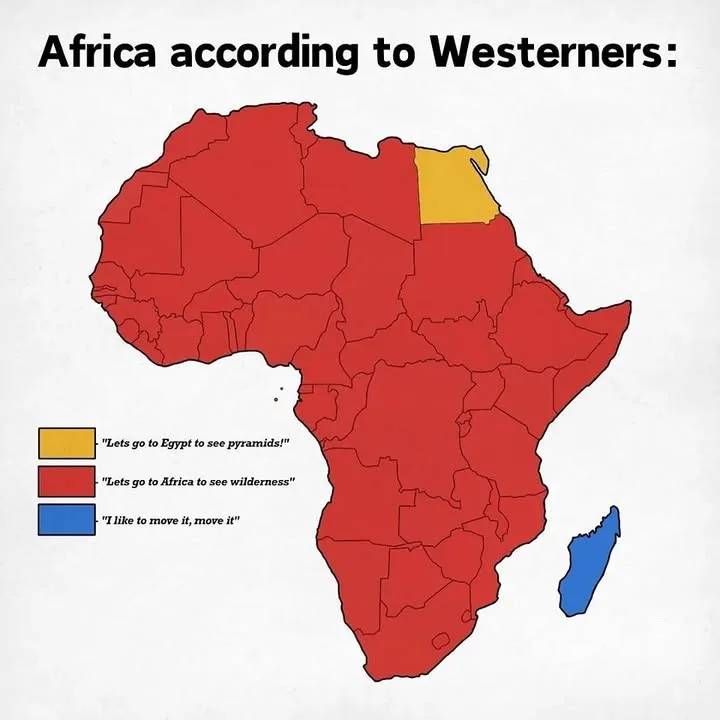

The perception of Africa among Westerners has historically been shaped by a complex interplay of colonial legacies, media portrayals, and cultural biases, often presenting a skewed or oversimplified image of the continent. Based on my knowledge and common trends up to August 31, 2025, here’s an overview of how Africa is frequently viewed by Western audiences, along with a critical lens to contextualize these perspectives.

Common Western Perceptions

A Land of Primitivism and Wildlife:

Western narratives often depict Africa as a vast, untamed wilderness teeming with exotic animals—elephants, lions, and giraffes—rather than a continent of diverse human societies. Media, including films like The Lion King or documentaries focusing on safaris, reinforce this image, sidelining urban centers like Lagos or Nairobi, which by 2025 boast populations exceeding 15 million and 5 million, respectively.

This stems from 19th-century colonial views, where explorers like David Livingstone framed Africa as a “dark continent” needing civilization, a trope perpetuated in modern travelogues and reality TV.

Poverty and Humanitarian Crises:

Africa is frequently portrayed as a continent plagued by poverty, famine, and conflict, with Western news cycles highlighting crises in regions like South Sudan or the Sahel. By 2025, while challenges persist—e.g., 430 million people still live below the $2.15/day poverty line (World Bank, 2024)—this narrative overlooks economic growth in countries like Ghana (6.9% GDP growth in 2023) or Kenya’s tech hub status, with Nairobi dubbed the “Silicon Savannah.”

Charity campaigns and celebrity-driven initiatives (e.g., Live Aid) amplify this focus, often ignoring Africa’s $3.1 trillion economy (IMF, 2025 projection) and its 1.4 billion people, 60% of whom are under 25.

Tribal and Traditional Societies:

Westerners often imagine Africa as a mosaic of “tribes” with unchanging customs, a view rooted in colonial anthropology that cataloged ethnic groups like the Maasai or Zulu. By 2025, this persists in popular culture—e.g., National Geographic specials—despite urbanization (60% of Africans projected to live in cities by 2030) and the blending of traditions with modernity, as seen in Lagos’s vibrant music scene or Johannesburg’s fashion industry.

This stereotype downplays pan-African movements and the legacy of figures like Kwame Nkrumah, whose ideas still influence continental unity efforts.

A Source of Exoticism and Resources:

Africa is often exoticized as a land of ancient mysteries—think pyramids of Giza or Ethiopian rock churches—while also being a resource hub for Western industries (gold, cobalt, oil). By 2025, the Congo’s cobalt, vital for batteries, drives $15 billion in annual exports, yet Western narratives rarely highlight local ownership or the 70% renewable energy potential (IRENA, 2024).

This dual framing echoes colonial exploitation, where Africa’s wealth was extracted under the guise of “civilizing missions.”

Historical Roots and Evolution

These perceptions trace back to the Scramble for Africa (1880s–1914), when European powers divided the continent, creating a narrative of backwardness to justify colonization. Post-1960s independence saw a shift to humanitarian focus, with Cold War proxy wars (e.g., Angola) reinforcing chaos stereotypes. By the late 20th century, globalization brought some awareness of African contributions—e.g., Egypt’s ancient innovations or Nubian kingdoms—but media often lagged, prioritizing sensationalism over nuance.

By 2025, social media and African diaspora voices (e.g., Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED Talk influence) challenge these tropes, with hashtags like #AfricaRising showcasing tech startups and cultural exports like Afrobeats. Yet, Western education curricula still devote less than 5% of global history lessons to sub-Saharan Africa (UNESCO, 2023), perpetuating outdated views.

Critical Reflection and Context

This Western lens often flattens Africa’s 54 countries into a monolith, ignoring diversity—e.g., Morocco’s Amazigh culture versus Somalia’s pastoral traditions—or progress, like Rwanda’s 8% annual GDP growth since 2000. It mirrors misinterpretations like the Coso Artifact or Eltanin Antenna, where initial assumptions (alien tech, human-dinosaur coexistence) were corrected by evidence. Similarly, Africa’s complexity—seen in Diodorus Siculus’ Ethiopian-Egyptian claims or the Dahomey Amazons’ ingenuity—requires a shift from stereotype to study.

Lessons and Modern Relevance

Like the Pantheon’s balanced doors or dendrochronology’s precision, understanding Africa demands effort:

Challenge Stereotypes: Recognizing Africa’s modernity (e.g., Kenya’s mobile money pioneer M-Pesa, used by 50 million by 2025) counters outdated narratives.

Cultural Exchange: Engaging with African art, like the Jadeite Cabbage’s craftsmanship, fosters mutual respect, akin to Samir and Muhammad’s unity.

Global Collaboration: Leveraging Africa’s resources and youth (median age 19) for climate solutions, as in HIMI’s preservation, benefits all.

A Tapestry Misunderstood

Africa, according to Westerners, is often a caricature of wilderness, poverty, and tradition, shaped by colonial echoes and media bias. Yet, by 2025, its reality—vibrant cities, tech innovation, and rich histories like those of Nubia or Mali—challenges this view. Like Claude Mellan’s single-line Sudarium or the black seadevil’s mystery, Africa’s true story requires us to look beyond the surface, embracing its 2,000+ languages and $3.1 trillion economy as a living testament to human resilience and diversity.