Thirty years ago, I wandered through Yemen, a land of ancient wonders and rugged beauty. In early 2012, as the country teetered on the edge of transformation, I felt compelled to capture that journey in words. The Arab world was reeling from a year of protests, violence, and upheaval, and Yemen was no exception. Ali Abdullah Saleh, the nation’s ruler for over three decades, was poised to step down—or so he claimed, signing away his power with a sly, almost cunning smile. Amid this thrilling yet unsettling flux, I wanted to preserve a piece of Yemen’s timeless past and my own memories of roaming through al-Yaman al-Sa’id, “Yemen the Happy.” This is the story of a city in the sky, a fleeting glimpse of that fabled happiness.

A Tale Lost to Time

The story I wrote was meant for a collection that never materialized. By September 2014, it hardly mattered. A new power swept through Yemen with force, swallowing its history in a grim present. The castles of my imagination crumbled like mirages, echoing Prospero’s fleeting towers. I stayed in Sanaa, surrounded by missile strikes and funerals, as the nightmare stretched on, unyielding even after six years.

In this distorted reality, light turns to shadow, and darkness takes form. Visiting a young neighbor wounded in the war, I saw the toll of a sniper’s bullet that tore through his wrist and out his elbow. His arm was a wreck, but I offered words of relief for his survival. “At least he didn’t get away,” he said, his face blank. “I killed him.” Above him hung an AK-47, its stock marked with a “Death to America” sticker. The Prophet once said Yemenis have the gentlest hearts, yet the tools of war—Kalashnikovs, Houthi drones, Coalition missiles—create distance, both physical and moral, from death. General Kalashnikov himself knew this, confessing to “spiritual anguish” in his final years.

This story reveals the shadow of the AK-47 over Yemen, a weapon that kills not just across space but across time, erasing identity itself. The castle in the sky I chased may be no more than a mountain man’s tale, a mirage on my mental map of Yemen. Yet, like peace, it felt solid enough at the time.

A Journey Through Raymah

It was over two decades ago, bouncing along a mountain track in a battered Toyota Land Cruiser packed with wiry tribesmen. The shrill wail of a mizmār, a double-reed pipe, blasted from the car’s speakers, mingling with the stale air inside. Outside, the sun burned hot, but the air was cold and crisp, sparkling in the high altitudes of Raymah, northwest Yemen.

Raymah’s mountains tower over the Tihāmah, the narrow Red Sea coastal plain 2,000 meters (6,600 feet) below, shrouded in vapor as the sun rose. Above us, peaks climbed another 500 meters (1,650 feet), their slopes terraced with sparse grain fields. Villages clung to the mountainsides, barely sustained by poor rains that year.

As we rounded a bend, a striking peak loomed into view, shaped like the sugar loaves sold in Yemen’s souks, wrapped in purple paper. Steeper than most, it stood bare, a brooding monolith framed by gentler slopes. “That’s Jabal Balq,” said the elderly Raymi man beside me, who’d been sharing local lore all along. The name evoked balaq, a fine white limestone, and another Jabal Balq near Ma’rib, home to the ancient dam and Sabaean capital. He nudged me. “There’s an ancient city up there, like a fortress.”

Legends of the Past

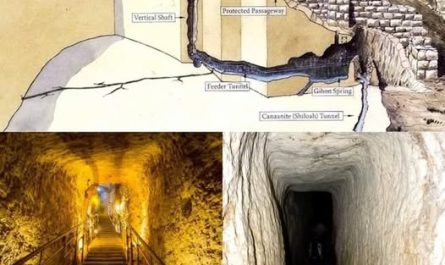

Yemen is a land of stories, where tales of Sabaean and Himyaritic ruins fuel an archaeology of the imagination. Some speak of Ād, a proto-Arab people from the Quran, or hidden caves brimming with Sheba’s treasures. Yemen’s real antiquities are stunning—the Ma’rib Dam, the walled city of Baraqish, the Baynun tunnel. Once, I explored a gorge filled with pre-Islamic rock-cut tombs, some still holding mummified remains. A villager offered to sell one, and I joked, “That could be your grandmother!”—the Arabic word for both is the same.

An ancient city in remote Raymah seemed unlikely, far from the pre-Islamic heartlands. Yet, as the saying goes, ahl makkah adra bi-shi’abiha—“the people of Mecca know its paths best.” The old man’s speech, with its archaic –k verb endings (jalask for “I sat”), echoed ancient South Arabian languages. Could he not also carry inherited memories of real ruins? There was only one way to find out.

At the Foot of Jabal Balq

Days later, I stood at Jabal Balq’s base with villagers whose homes lay in its shadow. They confirmed tales of ruins from the jahiliyyah, the pre-Islamic “age of ignorance.” One spoke of a castle with a rock-cut room, another of a tunnel through the mountain, emerging in the valley below. A tunnel through solid rock sounded like a fairy tale, but the Baynun tunnel—150 meters long, wide enough for a car—was real. “How do you get up there?” I asked.

A villager pointed to a faint crack winding up the near-vertical slope. “It’s not bad at first—there are steps in the rock. But higher up, it’s tough. At festivals, young men climb it as a dare.” Another added, “One fell and died a few years ago.”

My antiquarian adventure suddenly felt daunting. I asked about the tunnel. “Only one lad ever dared enter it,” a villager said. “He started at the top, and when he came out in the valley, his hair was white from fear.” Their faces showed no hint of jest—this was a cautionary tale. I mentally shelved Jabal Balq among unverified legends.

A Glimpse of the Past

One young villager lingered. “I can show you something else from the jahiliyyah,” he said. “It’s on Jabal Yaman, not far, and the climb’s easy.” In Yemen, “easy” is relative. Two grueling hours later, drenched in sweat, I reached a square opening in the cliff—a pre-Islamic rock-cut tomb, remarkable for Raymah’s once-forested slopes. The chamber was spacious, 4 by 5 meters (4.5 by 5.5 yards), with a man-length burial niche, empty in the gloom. I wondered who this Sabaean or Himyari figure was, buried so far from the highlands.

Outside, my guide pointed to an inscription above the entrance: a clear South Arabian Ḥ, perhaps a Y, then illegible marks, likely another Ḥ at the end. The rest had been destroyed, not by a pickax, but by “fools” on a nearby peak using the doorway for target practice with their AK-47s. The rifle’s precision had erased history, a loss as poignant as a fisherman’s tale of the one that got away. Yet, this was undeniably pre-Islamic, worth every drop of sweat.

Castles in the Clouds

What lies atop Jabal Balq? I still don’t know. Perhaps it’s best that some castles remain in the air, like peace, tangible only in memory. Yemen’s past, like its present, is a tapestry of beauty and loss, woven with threads of legend and truth.

Source: newlinesmag.com