The Rosetta Stone: Unlocking the Secrets of Ancient Egypt

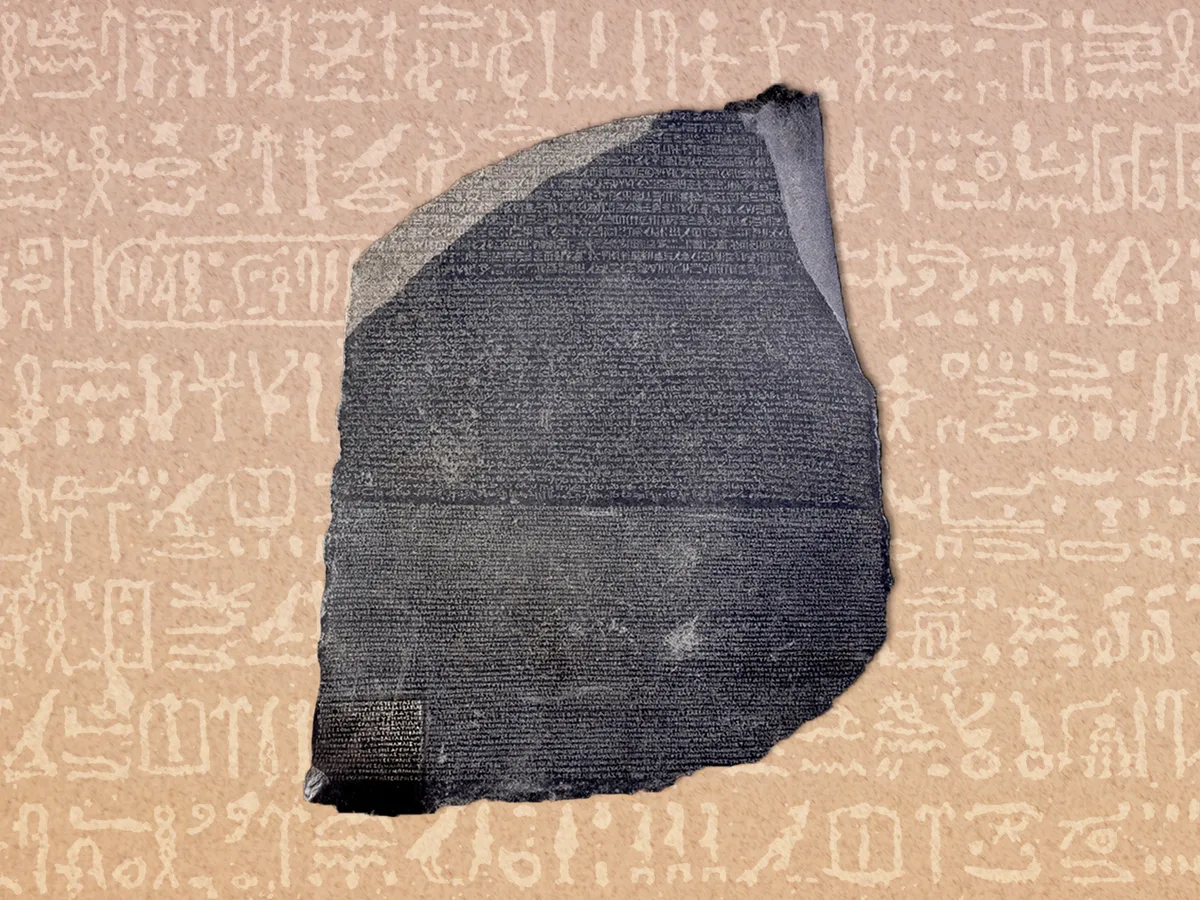

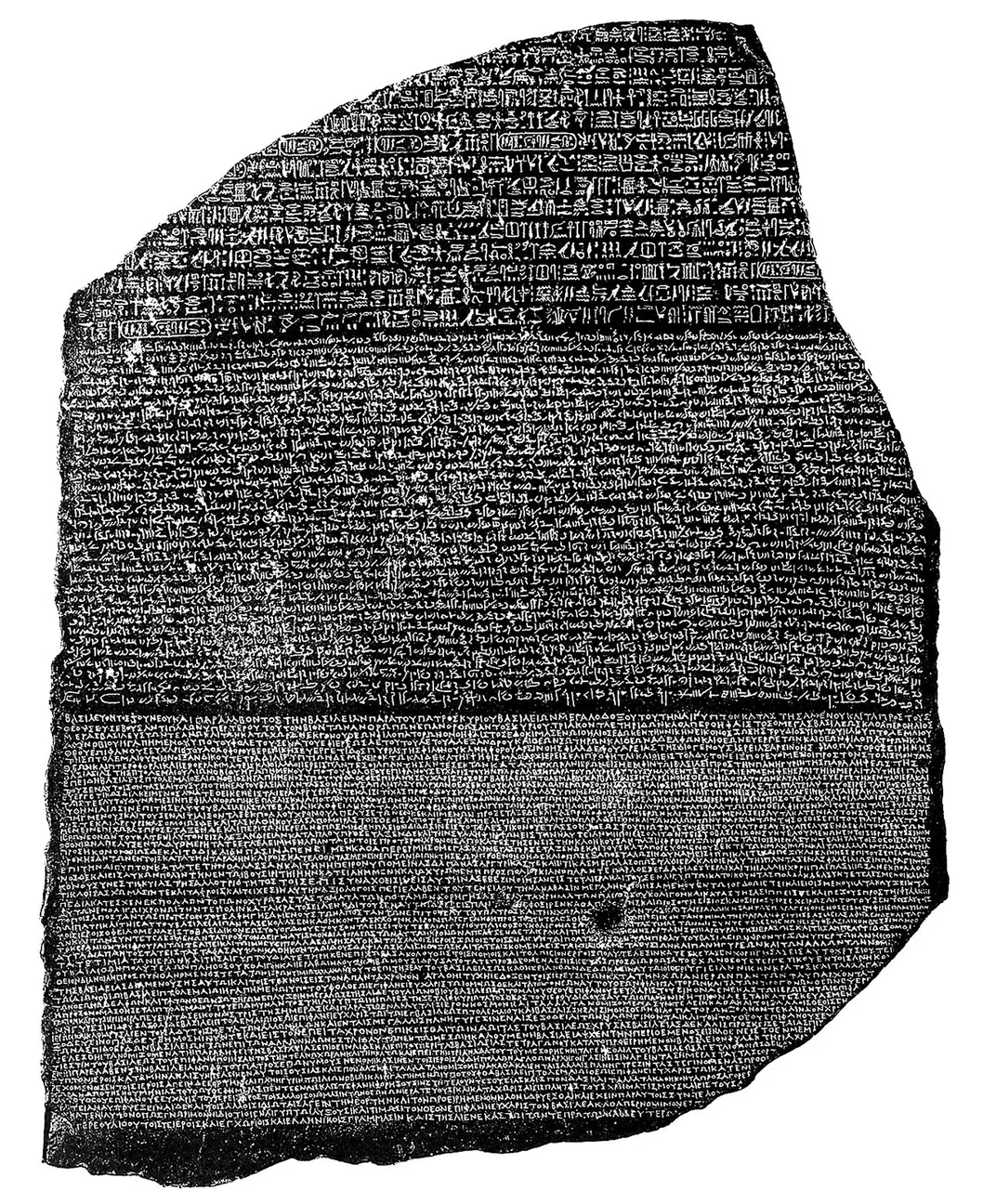

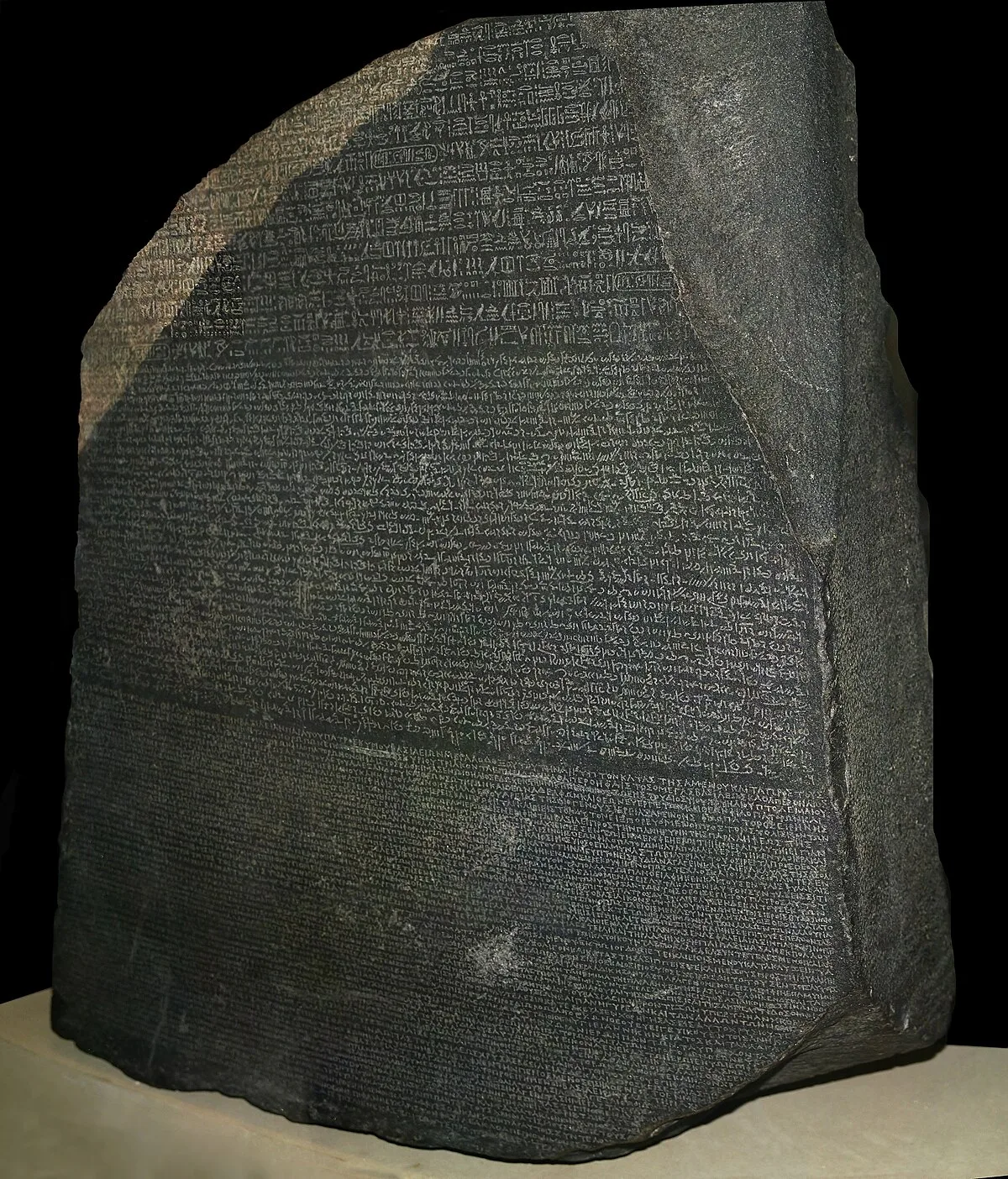

Discovered in 1799, the Rosetta Stone is one of the most iconic artifacts in human history, serving as the key to deciphering the long-lost language of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. Unearthed by French soldiers in Egypt, this unassuming granite slab, inscribed with texts in three scripts—Greek, Demotic, and hieroglyphs—opened a gateway to understanding the culture, practices, and societal structures of the pharaohs. Housed in the British Museum since 1802, the Rosetta Stone remains a cornerstone of Egyptology, revealing the richness of a civilization that thrived for millennia along the Nile.

Rosetta Stone

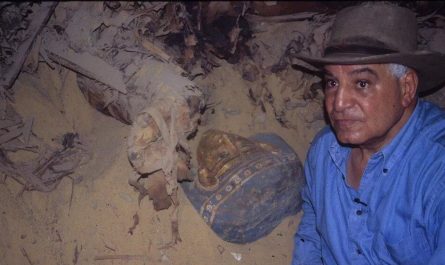

A Chance Discovery in Rashid

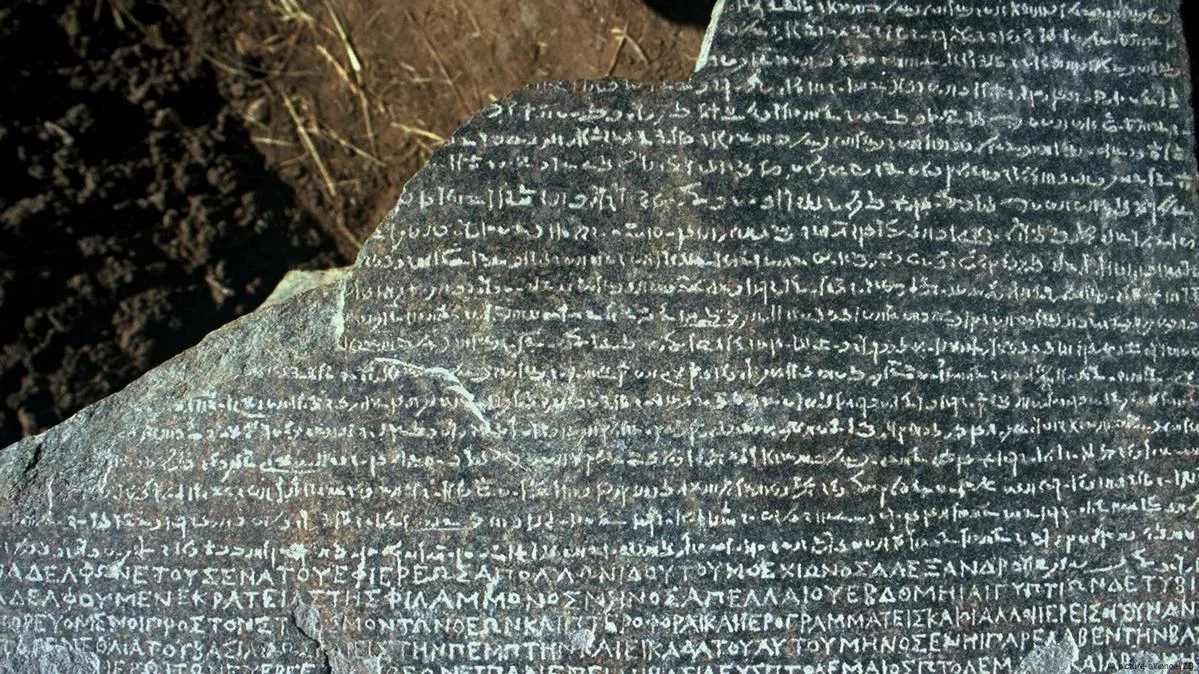

In July 1799, during Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign in Egypt, French soldiers stationed in the port town of Rashid (Rosetta) were fortifying a position when they stumbled upon a heavy, black granite slab embedded in a wall. Measuring about 1.1 meters tall, 0.75 meters wide, and 0.28 meters thick, the stone bore inscriptions in three distinct scripts: Greek at the bottom, Demotic (a simplified Egyptian script) in the middle, and hieroglyphs at the top. Recognizing its potential significance, the soldiers reported the find to their superiors.

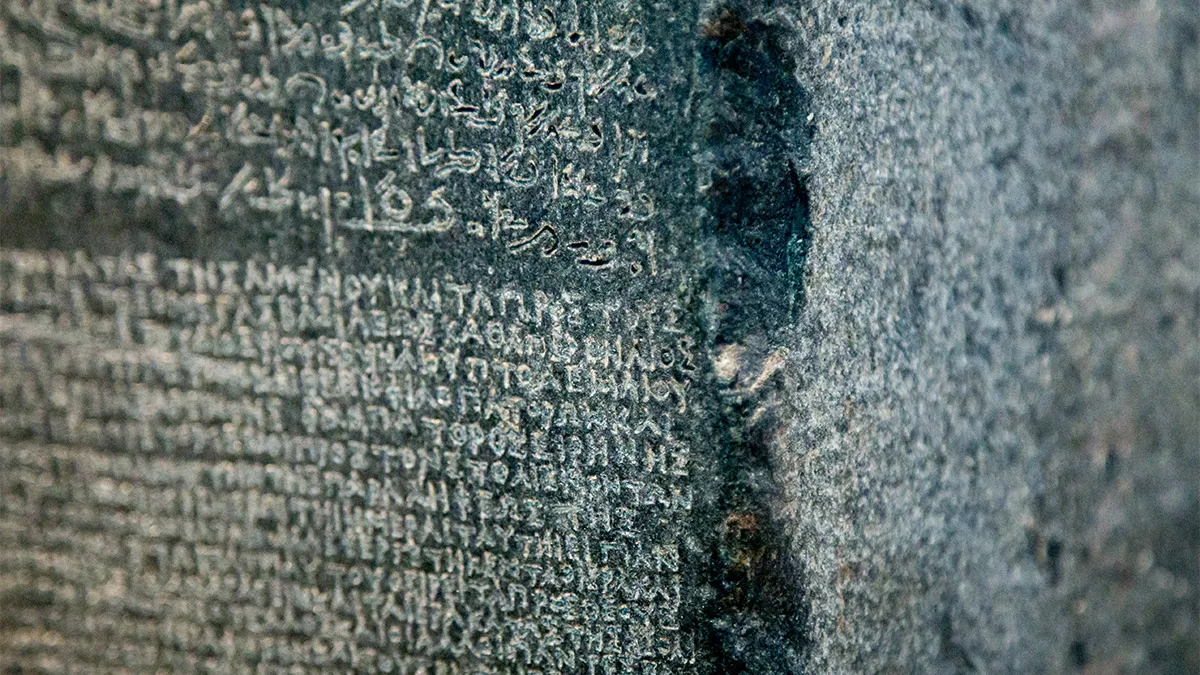

The Rosetta Stone, dated to 196 BC, records a decree issued by priests in Memphis honoring Ptolemy V, a Hellenistic ruler of Egypt. The decree, written in three languages to reach diverse populations under Ptolemaic rule, celebrated the king’s contributions, including tax exemptions and temple restorations. Its trilingual nature—Greek, a known language, alongside the then-undeciphered Demotic and hieroglyphs—made it an unparalleled tool for scholars seeking to crack the code of ancient Egyptian writing.

The Key to Hieroglyphs

Before the Rosetta Stone’s discovery, Egyptian hieroglyphs, used for over 3,000 years, were a mystery. By the Ptolemaic period (332–30 BC), their use had waned, and knowledge of the script was largely lost after Egypt’s conquest by Rome. The stone’s Greek text, readable by scholars, provided a crucial reference point, as it was assumed the three inscriptions conveyed the same message.

Decipherment was a collaborative effort spanning decades. English polymath Thomas Young made early breakthroughs in the 1810s, identifying that Demotic and hieroglyphic scripts contained phonetic elements, not just ideographic symbols. However, it was French scholar Jean-François Champollion who, in 1822, fully unlocked the hieroglyphs. By comparing the scripts and recognizing that hieroglyphs combined phonetic and symbolic signs, Champollion deciphered royal names like “Ptolemy” and “Cleopatra,” establishing a framework for translating countless other inscriptions. His work revealed that hieroglyphs were a complex writing system used for religious, administrative, and monumental purposes.

A Window into Pharaonic Culture

The Rosetta Stone’s decipherment revolutionized Egyptology, enabling scholars to read inscriptions on temples, tombs, and papyri. This opened a treasure trove of information about ancient Egyptian society, from the reigns of pharaohs to daily life along the Nile. Texts revealed details about religious practices, such as offerings to gods like Amun-Ra; political structures, including the power of the priesthood; and economic systems, like taxation and trade. The stone also illuminated the Ptolemaic era’s multicultural blend of Greek and Egyptian traditions, evident in the decree’s appeal to both communities.

Beyond its linguistic value, the Rosetta Stone provided context for understanding Egypt’s societal hierarchy, artistic conventions, and even medical practices documented in later discoveries. It helped scholars piece together chronologies of pharaonic dynasties and interpret iconic monuments like the Pyramids of Giza and the Valley of the Kings.

A Contested Legacy

The Rosetta Stone’s journey from Egypt to London is steeped in colonial history. After Napoleon’s defeat in Egypt, the stone was ceded to Britain under the 1801 Treaty of Alexandria and has been displayed in the British Museum since 1802. Egypt has repeatedly called for its repatriation, arguing it is a cultural treasure taken during colonial occupation. The debate reflects broader discussions about the ethics of museum collections and the return of artifacts to their countries of origin.

Despite its contested status, the Rosetta Stone’s impact is undeniable. It draws millions of visitors annually and has become a symbol of linguistic and cultural discovery. Replicas and digital studies ensure its accessibility, while ongoing research refines our understanding of its scripts and historical context.

A Lasting Symbol of Discovery

The Rosetta Stone stands as a testament to human curiosity and ingenuity, transforming an obscure slab into a key that unlocked an ancient civilization’s secrets. Its trilingual inscriptions bridged millennia, allowing modern scholars to hear the voices of the pharaohs and their subjects. As a monument to both ancient Egyptian governance and the 19th-century quest for knowledge, the Rosetta Stone continues to inspire, reminding us that even the most enigmatic past can be illuminated with the right key.