Mount Nemrut: Turkey’s Mysterious Monument of Giant Stone Heads

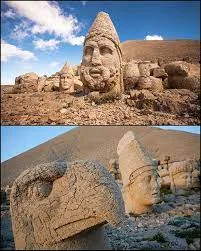

Perched at 2,134 meters atop the rugged peaks of southeastern Turkey, Mount Nemrut stands as one of the most awe-inspiring and enigmatic archaeological sites of the ancient world. Constructed in the 1st century BC by King Antiochus I of the Commagene Kingdom, this UNESCO World Heritage Site is renowned for its colossal stone heads—depicting gods, eagles, and the king himself—scattered across a windswept summit. Blending Greek, Persian, and Armenian cultural influences, Mount Nemrut reflects Antiochus’s ambitious vision to unite diverse civilizations under his rule. Yet, despite its grandeur, the site’s true purpose remains a mystery, captivating archaeologists, historians, and visitors alike.

A Royal Vision Carved in Stone

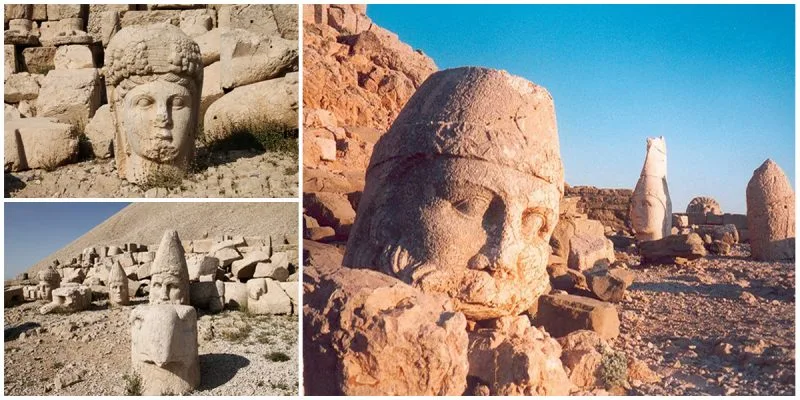

King Antiochus I, who ruled the small but prosperous Commagene Kingdom (163 BC–72 AD) between the Roman and Parthian empires, sought to immortalize his legacy on Mount Nemrut. The site, built around 62 BC, features two terraces—an eastern and a western—flanked by massive limestone statues, some standing up to 9 meters (30 feet) tall. These depict a pantheon of deities, including Zeus-Ahura Mazda, Apollo-Mithras, Hercules-Artagnes, and the goddess Tyche, alongside Antiochus himself and guardian animals like eagles and lions. Each figure is a syncretic blend of Greek, Persian, and local Armenian iconography, symbolizing the king’s claim to divine ancestry and his desire to bridge East and West.

The statues, originally seated on thrones, were accompanied by intricate reliefs and inscriptions detailing Antiochus’s divine lineage and religious decrees. A 237-meter-long artificial tumulus, a conical mound of loose stones, dominates the site, possibly covering a royal tomb, though no burial chamber has been conclusively found. The scale of the project, in such a remote and inhospitable location, underscores the resources and ambition of the Commagene Kingdom, which thrived as a cultural crossroads along ancient trade routes.

A Puzzle of Purpose

The true function of Mount Nemrut remains one of archaeology’s enduring mysteries. Several theories have emerged, each offering a glimpse into its possible significance:

- Royal Tomb: The tumulus suggests a funerary purpose, potentially housing Antiochus’s remains or those of his family. However, extensive surveys and limited excavations have found no definitive evidence of a tomb, leaving this hypothesis unconfirmed.

- Ceremonial Site: The terraces, oriented toward sunrise and sunset, may have served as a sacred space for religious rituals or festivals honoring the gods and the king’s divine status. Inscriptions refer to a new religious cult founded by Antiochus, blending Hellenistic and Persian traditions.

- Astronomical Observatory: The precise alignment of the statues and the presence of a lion relief with celestial symbols—interpreted as a horoscope dated to 62 BC—suggest the site may have functioned as an observatory or calendrical monument, tracking celestial events like solstices or planetary alignments.

Earthquakes over the centuries have toppled the statues’ heads, scattering them across the terraces and obscuring their original arrangement. This natural disruption, combined with the site’s isolation, has made it challenging to reconstruct its layout or confirm its purpose, adding to its mystique.

A Cultural Crossroads

Mount Nemrut’s statues are a striking testament to the Commagene Kingdom’s role as a melting pot of cultures. Antiochus, claiming descent from both Greek and Persian royalty, including Alexander the Great and Darius I, used the monument to project his divine kingship and unify his diverse subjects. The statues’ Greek-style facial features, Persian-inspired attire, and Armenian influences reflect a deliberate fusion of traditions, a hallmark of the Hellenistic period’s cultural syncretism. This blending is also evident in the inscriptions, written in Greek, which invoke both Olympian and Zoroastrian deities.

The site’s remote location, high in the Taurus Mountains, was likely chosen for its spiritual significance, offering unobstructed views of the heavens and a sense of divine proximity. The effort required to transport and carve the massive stones in such a harsh environment speaks to the kingdom’s wealth and the importance Antiochus placed on his legacy.

A Legacy Preserved and Explored

Discovered in 1881 by German engineer Karl Sester, Mount Nemrut gained international attention in the 20th century, earning UNESCO designation in 1987. Despite its fame, the site remains relatively understudied due to its inaccessibility and Turkey’s wealth of other archaeological treasures. Ongoing research, including geophysical surveys and 3D modeling, aims to uncover more about the tumulus and the statues’ original configuration. Preservation efforts are also critical, as weathering and tourism threaten the fragile limestone figures.

Mount Nemrut’s haunting landscape, with its decapitated gods gazing across the Anatolian horizon, continues to captivate visitors. The site draws thousands annually, particularly at sunrise and sunset, when the statues are bathed in golden light, evoking the grandeur of Antiochus’s vision. Its unanswered questions—Was it a tomb? A temple? An observatory?—only deepen its allure, inviting speculation about the ambitions and beliefs of a forgotten kingdom.

A Timeless Enigma

Mount Nemrut stands as a monument to human ambition, cultural fusion, and the enduring quest for immortality. Its giant stone heads, silent witnesses to 2,000 years of history, embody the Commagene Kingdom’s unique place at the crossroads of civilizations. As archaeologists continue to probe its mysteries, Mount Nemrut remains a powerful reminder of the ancient world’s complexity and the timeless allure of the unknown.